Out of Control: Chapter 19–Walkin’ Steel, 1991

Shortly after the new year, on January 16, 1991, the United States unleashed its military might against Iraq in Operation Desert Storm, or what’s often referred to as the First Gulf War. On March 2, 1991, Rodney King was brutally beaten by Los Angeles police. Such beatings were not uncommon, but this time it was caught on videotape for the whole world to see.

To us it was obvious that war and racism went hand-in-hand. We wrote a pamphlet to that effect and those of us in the Marion Committee joined in the anti-war protests, marching all over downtown Chicago and taking over Lake Shore Drive. Once more the powers-that-be did not seem to take note.

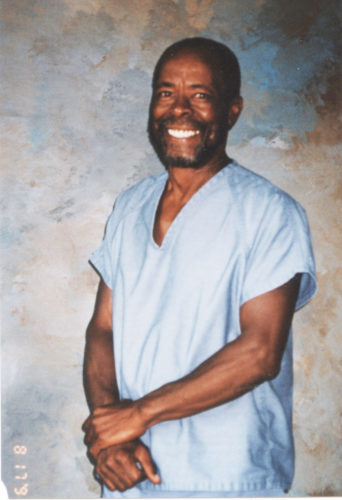

In 1991 I began another project. Through the process of producing the pamphlet about political prisoner Sundiata Acoli’s case, we became friends. In 1987 he’d been transferred out of Marion, perhaps in part because of our work, and moved to the federal prison in Leavenworth. I hadn’t been able to get permission to visit him at Marion, but now I could. I traveled to Kansas, staying with my friend, Paulette D’Auteuil, who was living there and working to free the Native American political prisoner Leonard Peltier. Together we went in and visited Sundiata and Leonard.

That visit led to a several-year collaboration between me and Sundiata as he refined his “A Brief History of the New Afrikan Prison Struggle,” now revised as “An Updated History of the New Afrikan Prison Struggle” and produced a yet-to-be-published autobiography. I found Sundiata to be a very strong, optimistic, and supportive individual who was meticulous about his work. He would send me the first draft of several pages in handwritten form. I would type it and send it back into him. He would then turn around and send me his revised copy. This process went on and on until he was perfectly satisfied. If he needed information he couldn’t get inside, I was an outside researcher. This was before the days of all-out internet access, so it was quite a production.

When we completed that project, he wrote his autobiography and we repeated the production process. The “Brief History” piece was finally produced on the outside in 1992, and was subsequently picked up by many others through the internet.

Ideally there is no conflict between fighting to change prison conditions overall and waging a campaign for the freedom of a particular prisoner. In the real world, however, there is a constant tension since we are always dealing with limited human and financial resources and energy. We tried to bridge that gap by giving voice to the prisoners as much as possible, particularly political prisoners. However, we often felt compelled to do more. Such was the case of Sundiata who I believe to be a real hero of the movement of the 1960s.

We produced a small pamphlet, “Sundiata’s Freedom is Your Freedom,” as a contribution to his freedom campaign. Born and raised in a small Texas town, Sundiata obtained a B.S. in Mathematics and worked in New York for 13 years as a computer programmer. In 1964 he read about the murder of the three civil rights workers—Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner. The article implied that the murders would deter volunteers from going south to register voters and listed the program contact. Sundiata called up and volunteered, paying his own fare to Mississippi, and spent the summer working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In the fall, he returned to computer programming, but felt that: “I couldn’t be proud of survival under the system in America, because too many of my brothers and sisters hadn’t survived… I was aware of the subtle pressures working to force upon me the acceptance of white values, to give up more and more of being Black… I loved being Black—the Black mentality, mores, habits and associations. I looked around for an organization that was dedicated to alleviating the suffering of Black people (from “Sundiata’s Freedom is Your Freedom”).

In 1968 Sundiata joined the Black Panther Party. The organization was targeted by the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and in 1969 Sundiata was arrested to stand trial in the Panther 21 case. The legal process took two years, the trial lasted eight months, and the jury took only 56 minutes to acquit all the defendants of every charge! Denied bond by the judge, Sundiata spent the entire two years in prison in what was essentially political internment.

Upon his release, he was constantly followed and harassed, and decided to join the clandestine movement. In 1973 he and two others were ambushed on the New Jersey turnpike. The incident that ensued resulted in the murder of Zayd Malik Shakur and the serious wounding of Assata Shakur. Trooper Werner Foerster was also killed by bullets of a state trooper’s gun. Upon Sundiata’s arrest, “a gang of New Jersey state troopers dragged me through the woods, through water puddles, and hit me over the head with the barrel of their shotgun. They only cooled out somewhat when they noticed that all the commotion had caused a crowd to gather at the edge of the road, observing their actions” (from “Sundiata’s Freedom is Your Freedom”).

Tried in an environment of mass hysteria, Sundiata was convicted despite the lack of credible evidence that he had even been involved in the shooting. At sentencing the judge stated that Sundiata was an avowed revolutionary and sentenced him to life and to 30 more years, to be served consecutively!

While we were in no position to lead a campaign to free Sundiata, living far from both the prison and the legal jurisdiction of his case, we did contribute to the campaign that others were waging on the east coast by publishing “Sundiata’s Freedom is Your Freedom.” It never felt like enough, but at least it was something. Sundiata is still in prison today (2012 [and 2018, ed.]) and remains a firm, uncompromising voice for Black liberation. Often, I am ashamed to say, I forget his birthday. He never forgets mine! On Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day, cards arrive like clockwork now addressed, as the years tick on, to the “Silver Fox.”

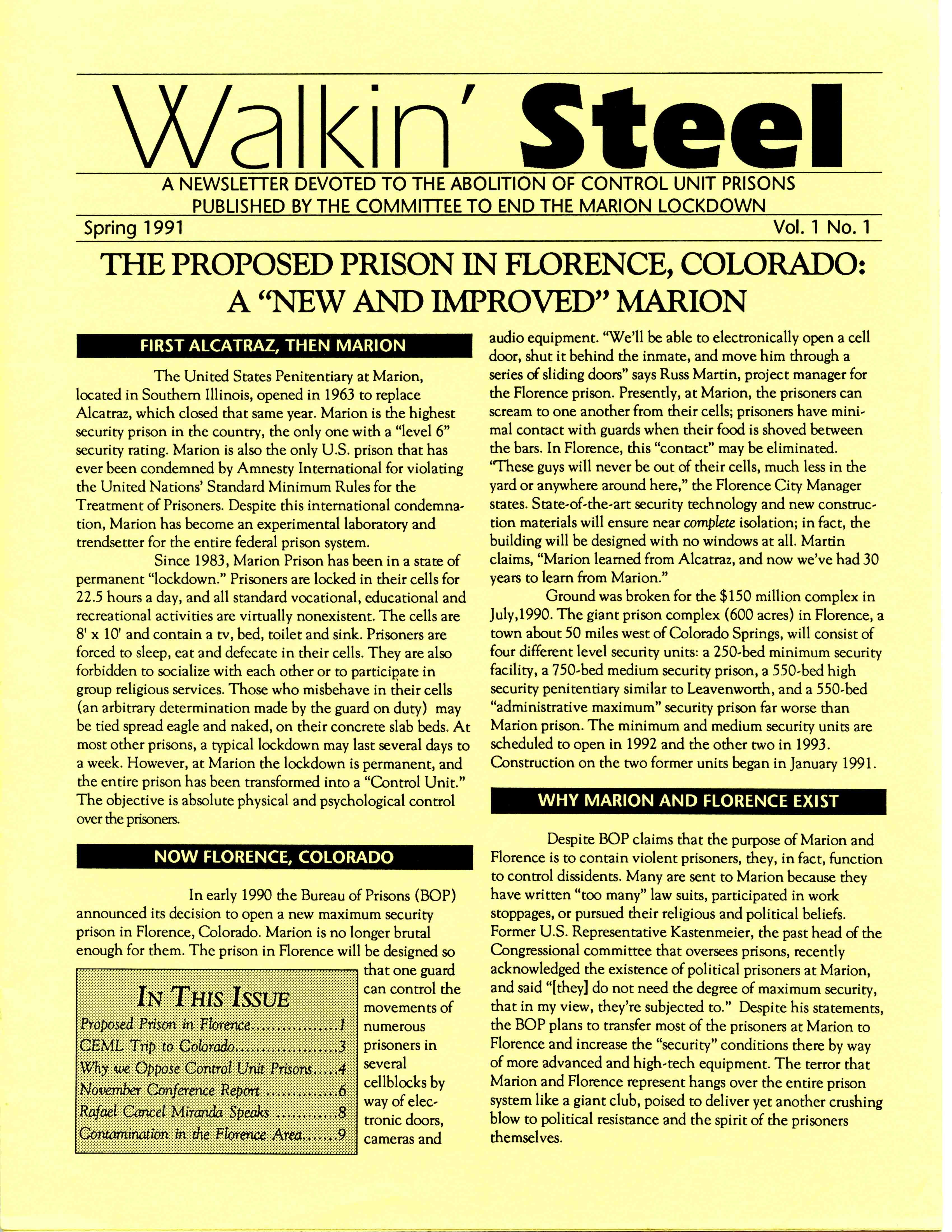

Since the beginning the Committee kept in excellent contact with our supporters through regular written reports. Now, in 1991, we decided to produce an actual quarterly newsletter. Batting around names, we agreed on Walkin’ Steel as suggested by Mariel. It had a poetic ring to it. The steel obviously referred to the prison itself, the gates sliding shut, the bars, etc. The “Walkin’”? Perhaps that we were now on the road, all the way to Florence, and more nationally-oriented. Or perhaps the “Walkin’” referred to what the prisoners would like to do. Or that, in lieu of freedom, at least our publication and their voices could get around.

At any rate, Vol. 1, No. 1, a 10-page issue, came out in early spring of 1991. Much of it was devoted to Florence, and we listed 12 organizations and individuals around the country fighting against control unit prisons. Our commitment to expand the work beyond Illinois required more effort on our part.

That spring we did not go to the prison gates in downstate Illinois. Mariel and I traveled to Colorado, she for the second or third time and me for the first time, to support the work around Florence.

We spoke in several places, including the University of Colorado, Boulder, attended a potluck luncheon organized by the Chinook Foundation (a fundraising group for progressive causes), and met with area activists to brainstorm about how to deal with the new prison.

Once more one of the greatest joys for me was meeting some wonderful people, most notably Edele Corrine. A registered nurse and activist with the Rocky Mountain Peace Center, Edele would become the most dedicated and essential Colorado organizer in opposition to the Florence control unit prison. She was studying the writings of a Vietnamese Buddhist and seemed to have a great mixture of gentleness and steely determination.

By the time we left the area, there were groups in Denver, Boulder, and Pueblo joining in the work. Our work had created ripples that were manifest in various ways. Michael Isikoff, staff writer for the Washington Post, did a lengthy piece on Marion (May 28, 1991, p. A6) in which he extensively quoted political prisoner Bill Dunne whom he described as an “articulate, self-described ‘anarchist’ who publishes lengthy tracts critiquing Supreme Court decisions and denouncing the ‘American Gulag Archipelago,’ a reference to the Soviet detention camps.”

Bill explained that, “You really have zero to do. It’s the endless repetition of the same day over again. There’s no community to connect with. If they see you getting too close to people, they move you into another unit. They want to make sure that you don’t have any bonding or any association with anyone else.”

That same month we heard from several sources that they had received letters from Warden Clark stating that if we in the Marion Committee ever visited the prison we would understand what a fine place it is and we would stop complaining. Up until this point we had assumed we would not be welcome. We still suspected that was the case but decided to take up the challenge. Steve wrote the warden a letter indicating that we were “delighted to learn of your desire to have us visit.” We did, however, have certain conditions, including access to speak with prisoners of our choosing or who chose to speak to us; unmonitored conversations; permission to question a representative of the prison (of course they could decline to answer any of our questions); and the recording of all conversations between our group and their staff.

Needless to say, a few weeks later we received a response from Warden Clark. It was a resounding NO! He saw no “common ground,” no “useful purpose” in a visit from us.

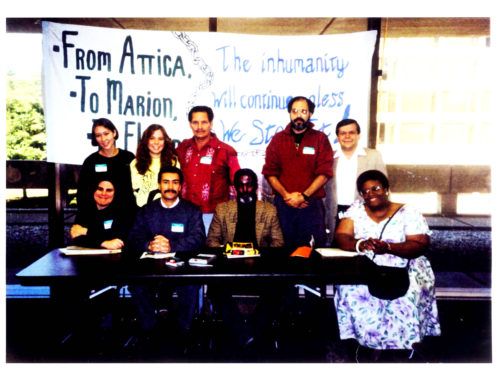

In September we held a day-long commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Attica Prison Rebellion of September 9–13, 1971, that included workshops, a strategy session about the control unit work, an evening rally and the showing of Shulamith Firestone’s prize-winning documentary film Attica. Finding a copy of the film was challenging. After some effort we did, however, track down what seemed to be one of the last remaining copies. The first thing we did was make copies to ensure its life.

Akil Al-Jundi, one of the Attica Brothers, was a keynote speaker. Akil was in the yard at Attica during the rebellion and had been struggling all those years ever since for justice. He was involved in the major civil suit on behalf of the prisoners that was finally to be heard that fall. After 20 years!

Michael Deutsch of the People’s Law Office was the other speaker. Michael, too, had been persistently fighting for the rights of the Attica prisoners. Our invitation stated that, “hopefully, we can take another step toward the creation of a united network.” In fact, the participants at the conference decided to devote a weekend of activities across the country, in Canada and Puerto Rico, to proclaim our opposition to Control Unit prisons, with an emphasis on Florence.

Those generating the activities would raise the issue of Florence, as well as whatever local issues were appropriate. Each location would choose the most logical site (local control unit prison, federal building, congressional office, etc.) and the most appropriate activities, whether demonstrations, press conferences, delegations, etc.

That fall we produced Walkin’ Steel Volume 1 Number 2, more familiarly known as the “grey issue.” It emphasized the proliferation of control units and was chock full of articles about Attica, Florence, and a piece by Safiya Bukhari Alston regarding “hidden” control units in upstate New York. The banner headline read “From Attica to Marion to Florence: The Inhumanity Continues Unless We Stop It.” We listed contact information for people around the country engaged in the fight against control units and included a powerful poem entitled, “Who Killed McDuffie?” by Hakim Al-Jamil, who had been a prisoner at Leavenworth.

In November, as we continued the work around Marion, and as the BOP construction was making fast headway in Florence, we were heartened to learn that Human Rights Watch, the international human rights group, had charged the U.S. prison authorities with engaging in “numerous human rights abuses” through the increasing use of “super maximum security” prisons modeled after Marion (Washington Post, Nov. 14, 1991).

After visiting more than 20 such prisons, Joanna Wechsler, director of the group’s prisoners’ rights project and chief author of the report, stated that she was “outraged at some of the incredibly harsh conditions…It’s practically impossible to forget some of the things we found.” Their press release of January 1991 further stated:

Human Rights Watch deplores the fact that 36 states have followed the example of the maximum security prison in Marion, Illinois, to create super maximum security institutions. The states have been quite creative in designing their own “maxi-maxis” and in making the conditions particularly difficult to bear, at times surpassing the original model.

As a result, inmates are essentially sentenced twice: once by the court, to a certain period of imprisonment; and the second time, by the prison administration to confinement in “maxi-maxis” under extremely harsh conditions and without independent supervision. This second sentencing is open-ended and limited only by the overall length of an inmate’s sentence and is meted out without the benefit of counsel. The increasing use of “prisons within prisons” leads to numerous human rights abuses and frequent violations of the U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

While our efforts were turning toward Florence, the situation at Marion seemed to be getting worse. Within several months of our request to visit, Warden Clark was no longer at the job.

A new Warden, Cecil Turner, had replaced him, and we were getting terrible reports from the prisoners. By December it was clear he was trying to make life even more hellish for the prisoners. Cells were “shaken down” frequently and without warning or reason, forced cell moves were common, arbitrary and sudden. Art materials were confiscated. Turner had lengthened “the program” that ostensibly governed a prisoner’s progress out of Marion, so most prisoners felt they wouldn’t leave Marion in time to avoid being sent to the new control unit at Florence in 1993. Some prisoners told us that they thought Turner was deliberately trying to cause a riot or some sort of incident.

In any event, tensions had risen sharply since Turner began this harassment, and we were still skirmishing with the prison regarding the water supply. We sent a letter out to all our friends asking them to write to the warden, as well as the Subcommittee protesting the worsening conditions at Marion. We added that in 1992 we would push for a Congressional Hearing and hold a weekend of protests and demonstrations May 2–3.

During this year (1991) we organized two campaigns regarding Florence: a petition campaign and a campaign to have the BOP answer a series of questions about the details of their plans for the new prison. We drew up a two-page set of 19 questions. After stonewalling for months, the BOP responded to our questions, but we felt their response was woefully inadequate, vague, and filled with half-truths at best and outright lies at worst. We still had no staff, no office, no money, nothing but our passion for justice and our own energy.