Out of Control: Chapter 5–Welcome to the Vortex

As I’ve said, we had told ourselves that this was an ad hoc, one-time conference, and that afterwards we would return to our other political work. But when it was over the energy and excitement that had been generated drew us in, and we could not bring ourselves to walk away. We also realized that no one else was taking on this difficult but necessary work.

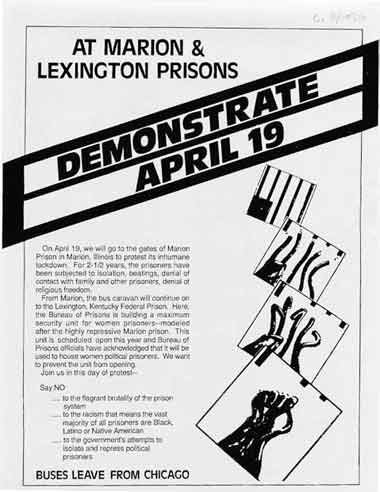

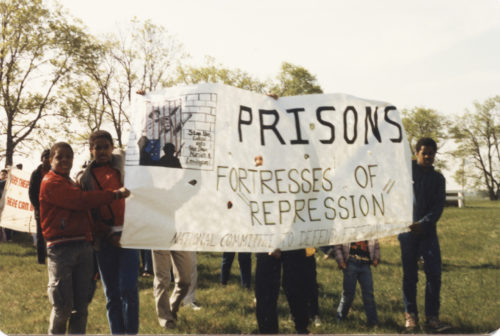

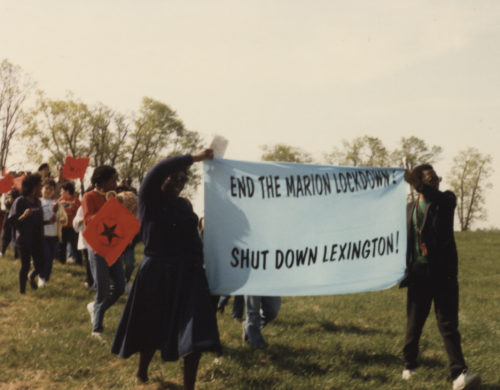

Soon after the conference, the National Committee to Free Puerto Rican Prisoners of War and the National Committee to Defend New Afrikan Freedom Fighters informed CEML they were planning a joint demonstration at Marion and Lexington, Kentucky on April 19th and asked for our participation.

The BOP had announced the opening of a new control unit for women at Lexington and had already acknowledged that it would be used to house women political prisoners.

On the heels of our conference, the John Howard Association, an Illinois prison reform group, released a 20-page report based on their recent inspection of Marion. We felt their observations and recommendations were mild, but welcomed them nonetheless as another voice of concern. More importantly, we doubted that without a grassroots, activist movement the Bureau of Prisons would be responsive to any observations, recommendations, etc. If a Congressional Subcommittee could not alter the situation, how could prison reform groups have an impact? The only way to proceed, we felt, was to build an actual grassroots movement that would be out in the streets demanding change.

We agreed immediately to participate in and co-sponsor the April 19th demonstration, with the idea that it might generate momentum and afterward other people would take up the cause while we went back to our other political work. This was, after all, an important opportunity not only to support the logistics of the demonstration, but also to organize around the issues that had motivated us to hold the conference in the first place. We knew it would be difficult, not only because we would have to convince other white people to attend this 30-hour demonstration at two prisons in two different states, but also because we would have to produce literature, hold many meetings, and provide financial support.

As our first step, we enlarged the committee by appealing to many of the people who had helped us with the conference. Each person we approached agreed to help—some joined the committee and others made it clear that while they could not work regularly on the demonstration, they would be willing and eager to attend and help whenever they could. We produced a pamphlet for the demonstration as well as a more general pamphlet about Marion and Lexington that would become a primary piece of literature in our work.

Up until now, everything had come out of our own pockets and there wasn’t much left in our pockets, so we had to do something else. In March we served a spaghetti dinner to raise money and showed The Brother From Another Planet, a great comedic yet serious movie by John Sayles in which an extraterrestrial who happens to be a Black man accidentally crashes his spacecraft in New York City.

Lots of people came from the Central America solidarity and peace movements. We believed that the people in this growing movement were natural allies in this prison work. Some of them had been to prison for acts of civil disobedience. Others shared our attitudes regarding issues of poverty and injustice. We argued in our flyer that:

. . .our own experiences participating in the anti-intervention, anti-apartheid, anti-nuclear, and disarmament movements have shown us that we also [like the prisoners] cannot rely on Congress or the courts to recognize or protect the rights of people when these rights are in conflict with the aims of the U.S. government. We have thus taken to the streets and demonstrated in order to expose human rights abuses caused by U.S. intervention in Central America and U.S. support for the apartheid regime of South Africa. For the same reasons we must take to the streets and demonstrate to expose and protest the human rights abuses which occur in U.S. prisons.

Sure enough, many people responded to our call and the starkness that was Marion. 130 people attended the dinner, far beyond expectations. We raised $400. Great, but nothing near the $10,000 we needed to pay for the buses and other expenses.

We asked several individuals, all of whom had spent time in prison and were well respected among activists, to help us out. Morton Sobell was a co-defendant of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and had spent 18 years in prison, five of those years at Alcatraz.8 All of these ex-prisoners—Daniel Berrigan, Rafael Cancel Miranda, and Morton Sobell—were glad to sign a letter calling on people to join us and provide financial support to the organizing effort. They argued that, “the demonstrations of April 19 are absolutely essential to prisoners across the country, to the antirepression struggle in general, and to the battles for national liberation being waged within the borders of the United States. In short, we can think of few political tasks more relevant that will be occurring in the next couple of months.”

The fundraising appeal to our friends proved productive and many people who were unable to join the caravan (and some who were able) donated a $60 seat for someone else.

We realized the mobilization wouldn’t succeed unless we were connected with people in Lexington and southern Illinois. With this in mind Steve and I made several trips to both places and met with many wonderful people who ensured the success of the activity. We left nothing to chance. We drove the possible route of the caravan more than once to determine which prison to go to first, where the pit stops might be, what the optimal times of arrival were, where to park, how to maximize visibility, how to contact local media outlets, what and where to eat, etc.

Steve was the most well known person at our neighborhood Kinko’s copy shop. When he arrived, he was greeted like Norm entering Cheers—“where everybody knows your name.” We held untold numbers of night-time meetings. Our kids had to adjust to this life as well. One night we were having a Marion meeting in our home when our eight-year-old son Michael walked into the room. “I’m hungry. Where’s dinner?,” he asked reasonably. “We’re so busy, Michael, can you possibly just grab some Cheerios?” Steve answered. Michael obediently trudged back to the kitchen returning only minutes later with a frustrated response—“there are no Cheerios!” There are many funny stories like this one but they indicate what a challenge it was to do this political work, support it financially, to raise our kids and—oh yes—go to work each day.

It pissed me off when people would yell “get a job” as we demonstrated, since we voluntarily took up this second job without financial recompense. In fact, we generally emptied our pockets. Steve and I probably spent $5,000 of our own money each year. He was an epidemiologist with a Ph.D., and I was a graduate student and then a social worker during the entire Marion work. This was an all-volunteer effort. We had no paid staff. We had no event planners. Every detail was up to us and our friends. I say all this not to pat ourselves on the back, but because I believe it’s important to explain the labor-intensive nature of serious political work.

The upside of the work, the joy of the work, is largely the company we got to keep. First of all, Steve and I were lucky enough to have one another. We loved spending time together while we planned the details. We loved working with José and Jan and getting to know them better. We loved meeting the many wonderful people without whom we would have been lost. In Marion and the adjacent town of Carbondale we met ministers, lawyers, professors, nurses, doctors, peace activists, and students, all of whom helped us in different ways with logistics, media, a pre-demonstration forum, and documentation of the events. And even my children, Rosa and Michael, benefited from the exposure to the work, dragged along to demonstrations and events, and meeting many interesting people along the way.