Out of Control: Chapter 2–Please Don’t Let Me Slip Away

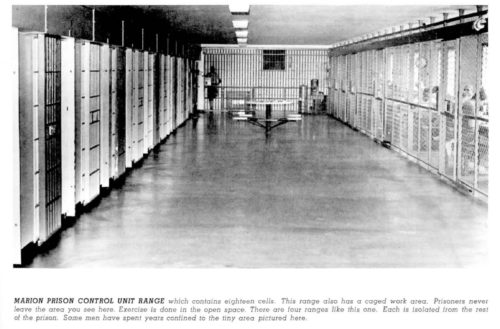

Marion Control Unit Range (Photo from Hell in a Very Small Place)

The men held captive in the Marion control unit lived in an 8 x 10 foot cell for about 23 hours a day, seven days a week. There was no contact with other human beings. There was no way to know when it would end. Days, months, years would go by. There was total idleness, no work, no education. The men were permitted to leave their cells for only an hour a day, to shower or to exercise in a special cage built for that purpose. Whenever they were moved, they were handcuffed and often shackled as well. At times they were shackled, spread-eagle to the cement block bed. They saw no people other than the guard who shoved the food through a slot in the wall of the cell. They were allowed one 10-minute phone call every three months and one two-hour visit per week from approved family members.

Families rarely visited because they lived and worked far away and couldn’t often afford the long trip, the time and the money, for a two-hour visit. And the visits were painful. There was no way to touch, hug, or kiss mothers, fathers, wives, or children. No physical contact was possible—talking was over a bugged telephone with a soundproof plexiglass wall between the prisoner and visitor. They were overheard and overseen by guards. Intense sensory deprivation and indefinite solitary confinement was the way of life. Prisoners obsessed over when, if ever, it would end. They sometimes pondered if they would go crazy. Some did.

You may wonder, is this a description of Guantánamo or Abu Ghraib? But no, it was and is the situation inside control unit prisons for many incarcerated people in the United States. This is not a new phenomenon. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons has been using solitary confinement and sensory deprivation systematically inside their prisons since at least the 1970s. They call these sites “control units” and they have proliferated throughout both the federal and state prison systems across the country. Indeed, in this day of debate about Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, it is absolutely essential to realize that a direct line extends from U.S. control units to these so-called “enhanced interrogation” centers throughout the world.

I had been living in Chicago for about a year when I heard the news that two guards had been killed by two prisoners in the U.S. Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, 350 miles south of Chicago. Although it was an isolated incident with no associated riot conditions, the prison was immediately placed on lockdown status, and the authorities seized on the opportunity to violently repress the entire prison population. For two years, from 1983 to 1985, all of the 350 men imprisoned there were subjected to brutal, dehumanizing conditions. All work programs were shut down, as were educational activities and religious services.

During the initial stage of this lockdown, 60 guards equipped with riot gear, much of it shipped in from other prisons, systematically beat approximately 100 handcuffed and defenseless prisoners. Guards also subjected some prisoners to forced finger probes of the rectum. Random beatings and rectal probes continued through the two-year lockdown. Despite clear evidence of physical and psychological brutality at the hands of the guards, Congress and the courts refused to intervene to stop the lockdown.

When Steve and I got together in 1985 sharing ideas became an important aspect of our new relationship. I was a part of a small, radical organization, and Steve was not. His perspectives seemed fresh, less influenced by our “group mind,” and I completely relished the give-and-take. One central topic of conversation was the U.S. prison system and particularly the situation at Marion.

I discovered that, in the early 1980s, when I was a legal secretary for radical attorney Len Weinglass in Los Angeles, Steve had been in Alabama working in support of the Atmore-Holman Brothers, a case stemming from an Attica-like rebellion. In fact, it was likely that he and I had talked about that case on the telephone.

We had both been tremendously moved and angered by the September 1971 events at Attica, a state penitentiary in upstate New York where 1,200 prisoners had occupied the yard, refusing to return to their cells and demanding humane conditions. After several days of negotiations, the state police, under orders from Governor Nelson Rockefeller, ferociously attacked the prisoners with firearms and gas. Twenty-nine unarmed prisoners and 10 hostages were murdered by the police assault force. Over 180 more prisoners were shot, some maimed for life and many others seriously injured. In addition, almost all the 1,200 prisoners were systematically beaten, made to run through gauntlets of club-swinging police as they were herded back to their cells. The United States Court of Appeals later called the aftermath “an orgy of brutality.” The courageous rebellion at Attica and the horrific response to the demand for human rights would motivate our work for years to come.

Steve had more recently been active in organizing support for the Pontiac Brothers, a group of African-American and Latino prisoners indicted in one of the largest death penalty cases in U.S. history, on charges stemming from a rebellion at the Illinois State penitentiary at Pontiac. I had helped organize an educational and fundraising event in L.A. for the Pontiac Brothers, and we both had been visiting political prisoners for several years.

We agreed that the nature of U.S. imprisonment had everything to do with structural racism in this country. Although Marion was at the Southern end of the state, the prisoners were largely from Chicago and other urban areas and the prison population was disproportionately Black. This repeated the pattern I had observed in the California prisons: prisons located far from family, friends, and community with disproportionate numbers of incarcerated people of color and predominantly white guards. The Blacker the population, the worse the prison conditions.

Although the terrible conditions at the prison were striking, what drew us to Marion in particular was the history of struggle of the prisoners and their allies on the outside. When the infamous Alcatraz was closed in 1962, Marion Federal Penitentiary was opened and became the new Alcatraz, the end of the line for the “worst of the worst.”

In 1972 there was a prisoner’s peaceful work stoppage at Marion led by Puerto Rican Nationalist Rafael Cancel Miranda. In response to this peaceful work stoppage, the authorities placed a section of the prison under lockdown, thus creating the first “control unit,” essentially a prison within a prison, amplifying the use of isolation as a form of control, previously used only for a selected prisoner. That was 1972.

At this time, in 1985, after two years of lockdown, they converted the whole prison into a control unit. Importantly, because Marion in 1985 was “the end of the line,” the only “Level 6” federal prison, there were disproportionate numbers of political prisoners—those who were incarcerated for their political beliefs and actions. These included people such as Native American Leonard Peltier who had spent years there until recently, and now (in 1985) Black Panthers Sundiata Acoli and Sekou Odinga (released from prison, November 2014), Puerto Rican independentista Oscar López Rivera (released 2017), and white revolutionary Bill Dunne. These were people we knew or identified with, activists of the 1960s and 1970s incarcerated for their political activities. Marion, like its predecessor Alcatraz and its successor ADX Florence, was clearly a destination point for political prisoners.

In September of 1979, when Black Panther Sundiata Acoli was imprisoned at Trenton State Prison, the International Jurist interviewed him and subsequently declared him a political prisoner. A few days later prison officials secretly transferred him in the middle of the night to Marion, even though he had no federal charges.

There was no rational reason why such people should have been sent to the worst prison in the country—no reason other than to punish them for their political beliefs and to isolate them in an attempt to thwart their influence on others. While one aspect of this was clearly an attempt to break the spirits of these and many other political prisoners, its purpose was also to send a strong message to general population prisoners about where they would end up if they challenged the conditions or nature of their confinement.

Next: Hell In A Very Small Place

About the Book | Table of Contents