Out of Control: Chapter 11–Joining the Work, 1988

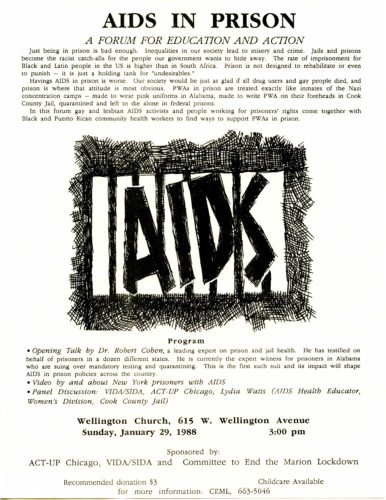

By 1988 the work was multifaceted, with many participants involved. In January we joined with ACT-UP Chicago to sponsor a forum on AIDS in prison. ACT-UP, a primarily gay and lesbian organization, was driving a movement to redefine how the world viewed the epidemic and gay people in general. In the process, people were open to rethinking many aspects of society, including the criminal justice system,and so were willing to join with us. We, in turn, were eager to show our solidarity with their fight. Ferd Eggan had been a key member of PFOC before quitting our organization, partly because of criticisms he voiced about our homophobia, and partly to work more effectively as a founding member of ACT-UP Chicago. Despite our differences, we were able to work together on this program and other activities. (Ferd passed away in 2007. You can read more about his extraordinary life.)

Many people continued to respond to the control unit work and make it their own. Dave Dellinger did not just speak at a program and then turn his back. He continued to use his platform to speak up about control units. From his home in Vermont, he wrote an article about Marion and Lexington for the March issue of Fellowship magazine entitled “Playing with Prisoners’ Minds.” Dave, a staunch pacifist, wrote the following:

Those of us who advocate and practice nonviolent methods of liberation cannot wash our hands of those who currently see no hope in such methods. As Gandhi said, “It is better to resist injustice violently than not to resist at all.” If some of the victims of our society and their supporters turn to violent methods, the fault is partly ours—for tolerating the society that victimizes them. And for having failed until now to develop nonviolent methods of resistance to—and liberation from—injustice, to the point where such people will be able to see nonviolent methods as more effective than the violent struggles in which a few of the prisoners at Marion and Lexington have engaged. One of the many areas in which to do this is in the struggle to close down the Marion and Lexington Control Units.

We were beginning to break through to the mass media. In February Dan Rather did an extended segment on CBS News. Danny Schechter, an activist I knew back in my 1960s yippie days, was now a producer for the ABC television newsmagazine 20/20. Danny was far too radical for ABC to last for long, but he did manage to produce a segment about Marion, “America’s Toughest Prison,” with Hugh Downs and Barbara Walters on March 18, 1988. The 20/20 reporter Tom Jarriel was actually granted access to the prisoners at Marion, and although the point of view of the prison bureaucrats was present in the report as well, the voice of the prisoners came across strong, sometimes chillingly. One prisoner reported:

I believe I spend most of my time dwelling on revenge. This is something that actually invades my dreams and, when I’m conscious, in my wakening hours. I realize it was just a dream and probably just the manifestations of my frustrations from being in here but I also realize there’s some guys going to be weak and they’re not going to be able to differentiate reality from dreams. And maybe when they leave here they might enact these dreams, see? And that’s why we speaking of madness—this is madness—because I have no business dreaming dreams like the dreams I have.

Jarriel also referred to the Amnesty International condemnation and interviewed David Hale, the former prison guard who offered:

I have been a prison guard for 13 years. I have beat inmates who have assaulted guards—they were aggressive inmates—but after the lockdown at Marion we went cell to cell and they beat inmates who were ideal inmates, had never caused the staff any trouble. It was just retaliation got out of hand.

The 20/20 piece prompted Michael Quinlan, Director of the Bureau of Prisons, to write a critical letter to Danny Schechter directly, which in turn led Danny to respond with a detailed 7½ page letter. Quinlan parried with a four-page letter of attempted damage control. While he was at it, he also sent off a letter to the President of ABC objecting to a Today Show’s piece on the Lexington Control Unit. (See letters).

It became clear that although the word about the inhuman control unit conditions at Marion was getting out, the federal government was making no move toward change, or even dialogue. On the contrary, they were digging in their heels and actively touting Marion as a model, actively promoting the proliferation of control units. As the 20/20 report revealed, 20 states were looking at Marion as a model.

In April the appeal of the denial of the prisoners’ class action suit was heard in the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. We printed thousands of flyers, distributing them throughout the city, and that morning we gave flyers to everyone entering the building for work, inviting them to the hearing. About 100 people joined us, and a good deal of media attention was generated. The Chicago Tribune, three TV stations and four radio stations, including NPR, all ran stories utilizing parts of our statements. Most referred not only to the barbaric conditions, but also to Marion’s special role in holding political prisoners and the racist nature of the prison system for which Marion was the capstone. We wrote “A Brief Report on the April 1 Appeals Hearing.”

Our spring “Dear Friends” letter remarked that we had watched the court proceedings, and “No decision had come down yet, but those of us who saw those three white men who will decide this case, and who have in the past ruled against the prisoners at Marion, are not optimistic.” We also let our friends know that we had published the entire transcript of our fall Tribunal, and it was on sale for $6. We asked for additional financial contributions to defray the costs of copies for prisoners.

Our mailing list was a treasure trove of wonderful people who we discovered whenever we had the opportunity to meet one of them. That spring, a man by the name of Bill Hayden with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in Detroit offered to host us on a Michigan tour. Bill had been involved in work related to criminal justice for years, but the immediate impetus for this trip derived from the fact that the Michigan Department of Corrections was just now opening a “super max” prison in Ionia explicitly modeled after Marion. We had been saying for quite some time that Marion would be a model and that we would see the proliferation of control units. This proved our prediction an unfortunate reality once again.

In Detroit, Bill had organized a 15-hour day for us. First there were interviews by both the News and the Free Press, as well as three radio stations. All the reporters commented on the difficult task facing us: “It’s a ‘lock ‘em up and throw away the key’ period.” “You’re trying to swim upstream against a tide that’s impossible to overcome; the mood of the country is for more and more prison construction.” The last reporter warned us that her editor would probably cut and change her copy anyway. It was as if they were defeated before they had even tried.

We then had a luncheon meeting with the National Lawyers Guild and an evening program co-sponsored by AFSC and Bishop McGehee. About 30 people showed up, which we thought extraordinary since we were up against the final game of the NBA championship, as well as stifling heat.

Wednesday was spent in Ann Arbor, Michigan with AFSC’s Penny Ryder and several others, and the evening in Lansing where about 20 people attended the program organized by the Michigan Council on Crime and Delinquency. We showed our slideshow, which stimulated a lively debate with the social workers, psychologists, attorneys, and paralegals in attendance. (See the full report on that trip as well as articles about our trip in the Detroit News and the Ann Arbor News.)

In May of 1988, Steve and I proposed to the Committee that we write a book about prisons entitled Out of Control. Individual chapters might be farmed out to prisoners and non-prisoners alike, but it would be edited by the Committee. By the summer people decided it was a pretty good idea, but felt it was too much work for the Committee. Steve and I accepted that decision, but decided to do it on our own. In addition to the general work of the group, and the rest of our lives, we now added one more significant project. For months and months, perhaps a year, we spent every “free” moment working on the book.

We wrote a proposal and sent it to South End Press. They agreed to publish it and assigned us an editor. Steve and I each interacted with various chapter writers. For instance, I worked with Sundiata Acoli on a piece about the Black struggle behind prison walls. He would send me handwritten pages that I would transcribe and then send them back to him. At times I would do research for him. We iterated back and forth until he was fully satisfied. That’s also when I researched and wrote my chapter about women and imprisonment. We were very disappointed when our editor left South End and the new editor wanted more control over the content of our book. Her political views differed significantly from ours, and so the project never came to full fruition. The unpublished introduction explained our view (still our view today) of the relationship between imprisonment, white supremacy, and social control. In my opinion, it stands the test of time and is still a thought-provoking piece.

While we agitated and educated about Marion, we noticed an interesting set of circumstances in our peripheral vision. A delegation of prominent Americans had traveled to Cuba to conduct an inquiry into present prison conditions and the treatment of prisoners in that country. This was the result of an agreement between a group from the U.S., the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), and a Cuban group, the National Union of Cuban Jurists (NUCJ). The NUCJ agreed to obtain open access to six Cuban prisons chosen by the U.S. delegation and to facilitate confidential interviews with prisoners, past and present. In exchange, IPS agreed to seek similar access to U.S. prisons for a Cuban delegation from NUCJ.

In February, the Cubans offered the American delegation unrestricted access. Following the trip, IPS issued a Preliminary Report. It was reported in the New York Times (May 31, 1988, p. 5) that the group found no evidence to support charges that torture, disappearances, or secret executions were practiced currently or in the recent past, although they did find certain conditions to be harsh and cruel, particularly the use of dark, cramped punishment cells to confine prisoners considered to be breaking or resisting prison discipline. They also concluded that most prisoners in Cuba work a regular work week at constructive jobs, almost all prisoners are paid the same wages as civilians, conjugal visits are well established, and prisoners are provided with education to bring them up to the ninth grade level.

What followed was interesting. The U.S. refused to reciprocate, denying the Cuban delegation access to American prisons. On May 12, John Whitehead, the Deputy Secretary of State, wrote to Adrian DeWind (who was an IPS Trustee, Chairman of Americas Watch, and former President of the Bar Association of New York) to say that four Cuban penal experts would not be granted visas to visit a number of prisons in the U.S.

However, DeWind and others fought back. A column entitled “Why Not Glasnost?” appeared in the New York Times on June 21, 1988, by journalist Tom Wicker, who years before had written a book about his experience as a witness to the 1971 Attica rebellion and massacre. An article also appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer by DeWind and another participant on the Cuba trip, Julia Sweig, entitled “America Bars Cuban Prison Experts” (June 25, 1988).

Wicker’s column stimulated an angry Letter to the Editor by the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights Richard Schifter in the same publication. (New York Times, July 11, 1978, p.A6)

Adrian De Wind and Aryeh Neier then responded to Schifter: “The demand that United States prisons be open to inspection by Cubans and others comes from Americans who believe that our Government should practice openness, giving us a better argument when we ask other governments to open up.” (New York Times Letter to the Editor by DeWind and Aryeh Neier, July 26, 1988)

This seemed to fall on deaf ears, as the Bureau of Prisons dug in their heels and closed off their prisons. That same month the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit ruled, as we had feared, against the Marion prisoners’ appeal, declaring that the conditions at Marion were indeed constitutional, even if they were indeed wretched, and thereby refusing to end the lockdown and the associated brutal conditions.

Warden Henman immediately held a press conference praising the court ruling. Of course, he wasn’t the only one to hold a press conference; we did as well. “At about the same hour in Chicago, prison critics blasted the prison as ‘an indictment of U.S. society’ comparable to conditions in South Africa,” reported the Southern Illinoisan (July 28, 1988, p. 1) Their article also quoted the Amnesty International report that “There is hardly a rule in the [U.N.] standard minimum rules that is not infringed in some way or the other.” In our press statement we warned people not to be fooled by the court’s ruling and to remember that “apartheid is constitutional in South Africa and the occupation of Palestine is constitutional in Israel.”

A week later the Southern Illinoisan printed a full page Guest Opinion piece by Steve entitled, “The Marion Penitentiary: It Should Be Opened Up, Not Locked Down” (Southern Illinoisan, August 7, 1988, p. 25). Steve reminded the readers that a study by the government’s own consultants indicated that only 20% of the prisoners had a security rating qualifying them for Marion. The other 80% could have gone to many other prisons.

Steve quoted the 1975 testimony of then-Warden Ralph Aron that, “The purpose of the Marion control unit is to control revolutionary attitudes in the prison system and the society at large.” Steve added that the District Judge James Foreman had said that, “In several instances [the control unit] has been used to silence prison critics. It has been used to silence religious leaders. It has been used to silence economic and philosophical dissidents.” Nothing about Marion has changed, Steve argued, except that now virtually the entire prison is a control unit.

A feature called “Southern Illinois Speaks,” a man/woman-on-the-street column, asked: “Do you agree with the court decision upholding the lockdown of the federal prison in Marion?” Of the five people, all white, two women and three men, only one man disagreed with the lockdown, saying, “It will only make things worse right in the middle of the summer. People are a lot more edgy in the heat of summer.”

In August, political prisoner Bill Dunne completed a handwritten 36-page document that included observations and reflections about Marion, as well as some information about his political perspective and incarceration.

Out in California on October 1, two women, Jo Babcock and Catherine Costello, opened an art installation entitled: “Marion: the New Alcatraz.” We had given them a good deal of information, and they wrote to thank us and let us know how their work was going. Amazingly, they had opened the installation on Alcatraz Island itself, now a park run by the National Park Service. The piece simulated non-contact prison visits with Morton Sobell and Leonard Peltier. Visitors entered a darkened room and sat down in front of a steely metal wall with two plexiglass windows in it. In front of each window was a telephone through which one could hear, on the one side, a taped message by Morton, and on the other side, a taped message from Leonard. Transcripts of the taped messages were provided as well. Jo and Catherine’s correspondence told us:

On the day of the opening, we were deeply honored to be joined by some A.I.M [American Indian Movement] people and other activists… A ceremony was held to bless our art piece and to ask that it help to bring understanding to those who see it. The traditional sage and sweetgrass were burned, and an eagle feather was passed as we prayed for all who are unjustly imprisoned, for the earth and the animals, and for all who are fighting for their liberation around the world. A friend sang a Leonard Peltier honor song.… We have gotten a tremendous amount of support for our work every step of the way, and now that the show has opened, we have spoke[n] to many people who want to understand more about U.S. prisons, political prisoners and the struggle of Native Americans.

Not everyone was happy about the installation. The supervisor for the National Park Service reported that the Bureau of Prisons was quite upset, and without consulting them, she censored the artists’ written statement, deleting a reference to the Amnesty International report. She further wanted them to remove the segment of the taped messages that offered addresses and telephone numbers to contact for further information. In their letter to us they stated, “After consulting with some other friends, we have decided to simply defy her request.”