Out of Control: Chapter 25–Our Eleventh Year, 1995

Meanwhile we continued the prison work, sometimes as the Committee to End the Marion Lockdown and sometimes as CCRIB, as part of the National Campaign to Stop Control Unit prisons. We spent a good deal of time in conference calls, having conversations with people doing the work in other places. The calls were set up by Bonnie Kerness of the American Friends Service Committee in New Jersey. I had never been on those kinds of conference calls, and I found them somewhat difficult and less than fully productive.

Always trying to be aware of eliciting and giving public space to the voices of prisoners, in the summer of 1995 we requested and received from Edele a list of prisoners in the Florence ADX. We wrote to each of them to see if they’d like to write a statement about what they had experienced there. We received about 10 responses which, in preparation for our October program, we typed, copied, and distributed as Reflections On the First Year of the Control Unit at Florence.”

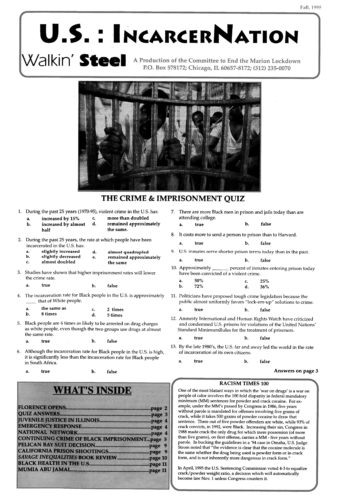

That fall we produced a new 12-page edition of Walkin’ Steel, Fall 1995. It included a clever quiz about imprisonment developed by CEML’s Tony Hintze that was subsequently picked up by numerous other publications. (The reader can view Tony’s reflections on his own imprisonment as a result of his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War.)

This issue of Walkin’ Steel was full of articles about Florence by our friends in Colorado, “The Continuing Crime of Black Imprisonment,” reports on the National Campaign, information on youth and imprisonment and women in prison, a piece by Mumia Abu-Jamal, and more.

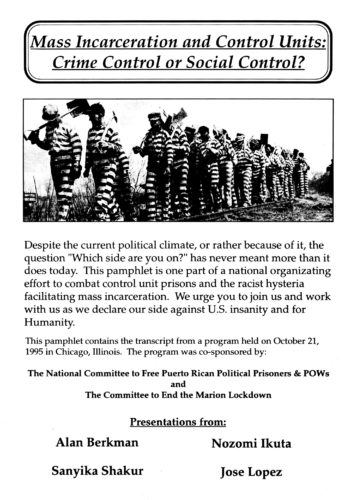

On October 21 we once again co-sponsored with the National Committee our annual fall program, the eleventh such program! We taped the evening program “Mass Incarceration and Control Units: Crime Control or Social Control?” then later transcribed and printed the remarks.

I began by reminding people that several years ago we in CEML had printed a statistic that one out of every four Black men in the U.S. was under some form of control—that is either in prison or jail or on parole or probation—and that the week before this program, the Sentencing Project in Washington, D.C., released a new study revealing that the proportion was now one out of every three Black men! In D.C. and Baltimore, the proportion, as reported the year before by Jerome Miller, was one out of every two Black men under some form of control.

The speakers that evening were Dr. Alan Berkman, Rev. Nozomi Ikuta, Sanyika Shakur, and Chicago’s (and Puerto Rico’s) own José López. Alan Berkman was an extraordinary man. When I first met him in the 1970s, he chose to practice medicine in places like the South Bronx and Lowndes County, Alabama where doctors were as scarce as in the poorest of Third World countries. In the ‘60s and ‘70s with the emergence of revolutionary movements, Alan used his experience and skills to support Black, Puerto Rican, and Native American movements. He was at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, during the historic occupation and confrontation between the U.S. government and the American Indian Movement.

In 1982 Alan was imprisoned for nine months for refusing to testify before a federal grand jury investigating the Black Liberation Movement. He was later indicted for providing medical care to a wounded revolutionary after a shootout with the police. Rather than allow himself to be incarcerated, Alan chose to elude the authorities and continue his political activities. In 1985 he was arrested in Philadelphia and charged with numerous indictments, including a series of political bombings of government and military targets. Alan was held in preventive detention for two years until his trial in 1987, despite the fact he was diagnosed with cancer. After conviction, Alan was sent to Marion Federal Penitentiary where he spent two years.

Steve and I had visited Alan when he was in jail awaiting trial in Washington, D.C. He was on a very heavily-guarded, locked prison ward of the hospital. Suffering from Hodgkin’s Disease, Alan was extremely frail physically, and we left feeling deeply frightened about his survival, but at the same time overwhelmed by his spiritual strength. He was alert, curious, and politically engaged.

In August of 1990 the BOP let Alan know that he would be returned to Marion despite his illness. That September Alan distributed a letter regarding his health, incarceration, and the attempt by the BOP to pressure him into becoming an informer.

In part due to a campaign for decent health care for Alan while in prison, he did manage to survive, and upon release continued to speak out for justice. His was one of the earlier voices on behalf of Mumia Abu-Jamal, and he later became a major fighter for affordable life-saving medicines to combat AIDS in Africa before his own death in 2009.

At our program October 1995 program Alan spoke about the control unit as a product of the Nixon Administration:

… in the face of urban rebellion by Black communities all over this country, crime was the way that politicians were going to have a discourse with white people about what to do with the insurgent Third World communities inside the U.S… it’s gone through several generations. “Law and order” became the “War on Crime” during the 1970s and became the “War on Drugs” during the Reagan Administration. Being “tough on crime” has become the way that politicians to this day discuss race relations with the white electorate. A key part of Bill Clinton’s electoral campaign was to leave New Hampshire in the middle of the Democratic primary and execute a mentally retarded Black man in Arkansas… George Bush… used Willie Horton to get elected. People in prisons are demonized and called subhuman. William Bennett, who was the Secretary of Education under Reagan… called prisoners “animals who should be beheaded.” Those of us who continue to reach out our hands to people in prison … are trying to keep those links of common humanity alive. (p.12–13 of “Mass Incarceration and Control Units”)

The next speaker, Rev. Nozomi Ikuta from Cleveland, Ohio, is just such a person who has reached out to prisoners. She was at the time Minister of Liberation Ministries at the United Church of Christ national offices, and a key member of the Interfaith Prisoners of Conscience Committee directed by Michael Yasutake. Nozomi had visited many political prisoners and had also been part of the National Interreligious Task Force on Criminal Justice that had gone into the new ADX prison in Florence. She had also become a critical part of our National Campaign Against Control Unit Prisons.

In the long run, I am not sure which is worse: the prison system’s creation of such an evil, or the public’s toleration (and worse, outright welcome) of it. After the heartbreak of Plexiglas separating prisoners from their loved ones and the knowledge of the strip searches and other forms of torture to which the prisoners will return, a visitor emerges from the Florence dungeon to a booming housing market and prosperity made possible by the very torture which takes place in that dungeon. (p. 17 of “Mass Incarceration and Control Units”)

Nozomi also candidly pointed out that in our attempt to build a national campaign “we were perhaps unrealistic in our initial plans, and suffered from the lack of an adequate structure to carry the campaign forward as effectively as we would have hoped.”

The third speaker of the evening was to be Sanyika Shakur. We had never met him, but his autobiography, Monster, detailed Los Angeles gang life and was on many bestseller lists. Two weeks before our program, Sanyika was released from Pelican Bay and was assured by the California Parole Board that he could travel to Chicago. At the last moment, however, the Parole Board reversed its decision, so his presentation came to us via a videotape we showed that night. As the brochure indicates, Sanyika described his emergence from thug-life to political awareness, from gang member to Black revolutionary. He noted over and over that his incarceration in California control units was a function of his political consciousness and behavior, not a result of any criminal activity. This transcription of “Mass Incarceration and Control Units” (p. 20–25) remains to this day one of Sanyika’s most eloquent expositions of his political growth.

José López’ speech that evening was wide-ranging and should be read in its entirety (“Mass Incarceration and Control Units,” p. 26–33). Comparing prisons and university graduate programs, he noted:

If there are right now 1.5 million people in prisons and jails in this country, and nearly 70% of those people happen to be people of color, and there are 1.5 million people at the graduate level of higher education across the country, and if about 80% of those graduate students… happen to be white, there is a real bell curve in America. Without a doubt, America’s prisons reflect America’s reality.

He added that denying people their freedom will never resolve the underlying problem. Historical problems, like individual problems, insist on being resolved. For example, an individual’s deep psychological problem will keep on surfacing until it is resolved. So it is with historical problems. He pointed out that in 1902, W. E. B. DuBois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.” José asserted that as we enter the 21st century, the problem still seems to be the color line.

José agreed with Nozomi that thus far our successes had been small ones, yet he also encouraged us to continue the work, to continue to collectively imagine the possibilities. “Freedom is nothing more than the possibility of human beings understanding the world about them, acting responsibly upon that world and, most importantly, transforming that world.” (“Mass Incarceration and Control Units,” p. 32)

The same weekend as the “Mass Incarceration” program, in a coordinated activity, we held the second meeting of the National Campaign to Stop Control Unit prisons, with about 40 people traveling to Chicago from places as far away as New York, San Francisco, Boston, Denver, Dayton, and Newark. The National Campaign really had difficulty getting off the ground in the year between the first meeting in Philadelphia and this one in Chicago. We had hoped for a national action to take place, perhaps in Washington, D.C., but although people were doing work in their local areas, not much common, coordinated activity had taken place. The potential power of a national organization had not been realized, but we were persisting in the hopes that it could be realized in the future.

After almost a year of informal discussions, the second national meeting of the National Campaign was held in Chicago in October of 1995. CEML offered an action proposal that recognized our inability to carry out an effective protest in Washington at that time.

We were lacking in financial resources and in human resources in the D.C. area. The group settled on a seven-month plan that would culminate in coordinated regional activities in opposition to control unit prisons in the spring of 1996. Our Midwest Region would produce a newsletter for the campaign. I volunteered to work with Bonnie Kerness from the American Friends Service Committee in New Jersey to develop an Emergency Response Network, an e-mail network that could respond on short notice to emergency situations within the prisons.

In November of 1995 prisoners around the country rocked the federal prison system in response to Congress overriding the recommendations of the U.S. Sentencing Commission to equalize the extremely disparate penalties for crack and powder cocaine, the latter used overwhelmingly by white people. Eighty prisons were placed on lockdown. We called for people on the outside to do something: Urgent Action Required. The firebrand attorney William Kunstler had died just weeks before, and in Chicago a celebration of his life was organized by local Attorney Ted Stein and others. I spoke about Bill and linked his spirit to that of the rebelling prisoners, calling on people to take up his mantle.