Out of Control: Chapter 4–Our Work Begins, 1985-1986

It seemed imperative to do something before the lockdown became set in stone. We were terrified that if Marion became an accepted model that proliferation would inevitably follow. We saw Marion as an experiment. We believed they were trying the experiment out—not only on the prisoners who were being held in these cages and tortured—but also as an experiment being perpetrated on the American public, through Congress, the courts and areas of public opinion. If these horrific conditions could win public acceptability, then the government would establish control units everywhere.

Unfortunately, our predictions turned out to be absolutely right, and even an underestimation, because, as I will document throughout this piece, control units have proliferated not only throughout the federal system, but also in virtually every state in the United States. It is remarkable to think that when we started doing this work in 1985 not one state in the U.S. had a control unit prison. Now virtually every state has at least one. Furthermore, in a progression we never could have envisioned, the model has now spread throughout the world— Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, etc.

Steve and I looked around to see who on the outside [of the prison] was doing the work in the hopes of joining their efforts. The Marion Prisoners’ Rights Project by now was a group in name only. The valiant lawyers at the People’s Law Office in Chicago—Jan Susler, Dennis Cunningham and Michael Deutsch—were filing legal actions on behalf of the prisoners and their attorneys and paralegals, who had been banned from entering the prison, falsely accused of encouraging a work stoppage. They were also monitoring the situation and issuing continuous reports. There were also some individuals in southern Illinois who were visiting prisoners, and attempting to lend support, but they were reluctant to become more active for fear of being denied visiting privileges. The lawyers were trying to carry the banner, but had no larger, organized group to engage in the political and educational work.

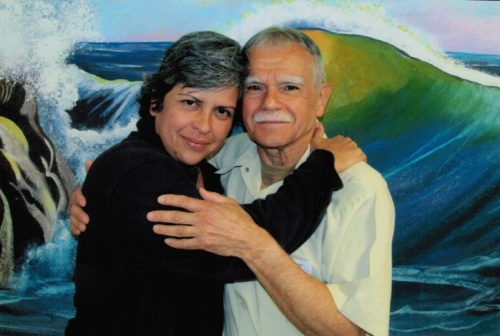

Steve and I were both involved in other political work, but we met with attorney Jan Susler to brainstorm about the situation and see if there was something we could do. I had met Jan a year or so before in the back of a pickup truck when we traveled with our Puerto Rican compañeros to a massive May Day march in Juarez, Mexico. I was impressed by this youngest representative of the People’s Law Office. She was definitely a “people’s lawyer.” No aloof attorney, she threw herself right into the fray of activities with everyone else. Friendly, sharp and political—and a woman!

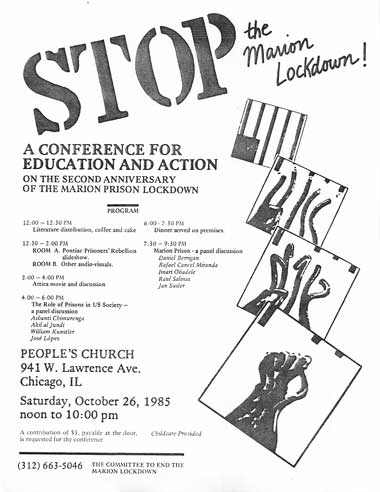

We were all three concerned about the situation at Marion (Jan had already been involved with a great deal of congressional work regarding Marion) but we all had other priorities that engaged our time. Jan was spending much of her energy trying to free the Puerto Rican political prisoners. Steve and I were involved in anti-war work regarding the U.S. involvement in Central America, and I had commitments to the radical Prairie Fire Organizing Committee as well. Not to mention our day jobs. Given this, we first agreed to organize just one activity on an ad hoc basis. It would be an afternoon and evening “Conference for Education and Action on the Second Anniversary of the Marion Prison Lockdown.”

We ran the idea by José López, our friend and in many ways political mentor. He was national coordinator of the Puerto Rican organization, the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional, director of the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, and had been imprisoned for seven months for refusing to testify before a grand jury investigating the Puerto Rican independence movement.

José was born in mountainous San Sebastian, Puerto Rico on a small farm without running water, electricity, or indoor plumbing. He moved with his jibaro family to Chicago at the age of nine. José’s mother, who never learned to read or write, was full of Puerto Rican history, literature, poetry, and politics. José developed his own love of history and went on to graduate from Loyola University, becoming a professor at several Chicago area colleges. He has been a key player in the creation of a Puerto Rican zone around Division Street in Humboldt Park where the community is attempting to stave off the drive toward gentrification. As the Executive Director of the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, José has been essential in imagining and developing a whole network of organizations in the Humboldt Park Community, among them the Don Pedro Albizu Campos High School, Centro Infantil Consuelo Lee Corretjer, VIDA/SIDA (an AIDS project), Cafe Teatro Batey Urbano (youth space), the Puerto Rican Institute of Art and Culture, and the Empowerment Diabetes Center.

José has also been a leading proponent of Puerto Rican independence here on the mainland and one of the most prominent voices for freeing political prisoners, including of course the Puerto Rican political prisoners. Finally, José is well known for always working “24-7” for a better world and for inspiring many of us to come along with him in the pursuit of this endeavor. José had, and still has, a profound effect on many of us white radicals who have had the opportunity to work with him.

In our corner of the movement, we felt we had a particular responsibility to organize other white people to fight racism and injustice. For instance, in the very segregated city of Chicago we would set up literature tables in predominantly white neighborhoods and seek opportunities to speak at churches with predominantly white congregations. Sometimes other leftists would argue that we were racist because of this stance. However, they missed the essence of our politics. We were the furthest thing from white separatists. We thought it was important not to compete with the self-organization of people of color, and everything we did was in close consultation with activists in those communities. In addition, we tried to support the agendas that were developed by those activists. For instance, while some people argued that it was unwise to link the issue of the freedom of political prisoners to that of the control units, we felt it was necessary to address both at the same time.

This first conference was an example of that collaboration, one that would unfold for the next 15 years. Before any plans were finalized, we ran the idea of the conference by José who loved it and agreed to participate as a speaker, recalling that Puerto Rican national hero Rafael Cancel Miranda had spent years at Marion and was a leader of the 1973 work stoppage. Now José’s brother, Oscar López Rivera, was one of a group of younger Puerto Rican political prisoners incarcerated for their activities as independentistas. López, arrested in 1981, was and still is serving a sentence of 70 years for seditious conspiracy, for his commitment to the independence of Puerto Rico. He was not accused or convicted of causing harm or taking a life. His projected release date is in 2023.

We all knew there was a strong chance that Oscar would end up at Marion and within months that prediction came true. For that reason, and because they understood the nature of imprisonment in the U.S., the Puerto Rican activist community in Chicago became essential allies, often the driving energy, in the work around Marion.

After much discussion we developed a call to the conference, a piece of literature that argued that prisons are a tool of social control and that the problems are societal, not individual. We proclaimed in our call to the conference:

Dostoevsky [Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky] wrote that to understand a society, one should look within its prisons…[We agree. In fact,] a majority of all prisoners are Black, Hispanic or Native American. The society that delivers such a disproportionate number of Third World people to the prison doors is one that has produced a generation of Black and poor youth, 75% of whom are unemployed, who are trapped in deteriorating public housing projects, who drop out of school at alarming rates, who lose their lives to drugs, crime and violence.

… Prison authorities drop the guise of being rehabilitation-oriented and endorse the warehousing model; instead of educational/vocational programs, they add more guard towers, more barbed wire, more restrictions. The message is that crime is caused by bad individuals, implying that by caging and electrocuting them, the society will somehow be healed. Our attention is turned away from the real causes of crime. Instead we are encouraged to blame the individual—and since most of the blaming is directed toward Black people, this leads to the criminalizing of an entire people.

It was remarkably easy to put together a speakers list. Everybody we asked to participate was more than willing to help. I picked up the phone and called my old friend attorney Bill Kunstler who accepted the invitation without even thinking about it. Steve contacted Daniel Berrigan, the priest who had been imprisoned for anti-militarist actions and wrote Hell In A Very Small Place. He agreed immediately as did Akil al Jundi, one of the Attica Brothers organizing support for the lawsuit seeking justice following the 1971 prison rebellion.

Several of the speakers knew about Marion from painful firsthand experience. Puerto Rican Nationalist Rafael Cancel Miranda agreed to travel from Puerto Rico for the conference. Imari Obadele, founding president of the Republic of New Afrika, had also spent time at Marion, stemming from an armed assault on him by Mississippi police. Raúl Salinas had also been a Marion prisoner and was a spokesperson for the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee. Two women attorneys would speak, our own Jan Susler from the People’s Law Office, and Ashanti Chimurenga, coordinator of the New Afrikan Legal Network.

Although an “ad hoc” event, the conference was substantial. It ran from noon to 10:00 pm. There were two sets of workshops: one about the general role of prisons in U.S. society; the other more specifically about Marion. William Kunstler was unable to attend due to a conflicting court date, but our good friend Attorney Michael Deutsch did a great job in his stead. Michael had litigated for years against the inhumane conditions at Marion, in addition to his work on Attica and Pontiac. There was a slideshow about the Pontiac Prisoners Rebellion and a movie about Attica. We provided childcare for participants and a full dinner was prepared by the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee.

We were quite satisfied with the conference as a first step. We were garnering attention and support. The week before the Chicago Reader ran a full-page article “Conference Calls: What’s Cooking at Marion Prison?” Over 300 people attended and there was lots of energy. The conference built a fine spirit of solidarity among its participants and—most importantly, in Rafael’s words, deepened a determination to “do something!”