Out of Control: Chapter 14–Toxins on Tap, 1989

At the start of the new year, 1989, Steve wrote an angry letter to Warden Henman on behalf of CEML protesting the censorship, once again, of our mail to the prisoners. Every year we solicited, produced, and distributed copies of the prisoners’ reflections on the lockdown at our fall program. That year we sent copies of these “Reflections on Five Years of the Lockdown” to 27 prisoners at Marion.

However, all of the prisoners informed us that they had never received the “Reflections.” What’s more, CEML had not received any return mail. This was not the first time we had to fight the prison on the censorship of mail. Steve’s letter accused them of continuing their “arbitrary and abusive manner of running that institution . . . We know that you will have many lies to tell about how these 27 letters managed to get ‘lost,’ but we nonetheless eagerly anticipate hearing from you.”

To their credit, two weeks later they sent us a reply. To their discredit, they reported that the staff investigated and “found nothing to indicate these documents have been rejected or otherwise prevented from coming into the institution. Rather it appears these documents, if ever mailed, are most likely in the possession of the inmates to whom they were mailed.” He reminded us that the courts did not agree with us that the prison administration was “arbitrary and abusive,” and he warned against placing credence in the word of those incarcerated.

In other words, never believe anything a prisoner tells you. It seemed absurd to us that all 27 of the prisoners would lie about such an occurrence, especially considering how difficult it was to communicate with each other inside. And to what end? All of the prisoners were interested in seeing the document. We had known some of them for years, even before their imprisonment, and others we had no reason to doubt. We were living in parallel universes, the BOP and the CEML.

By now it was clear that victory in getting the prison off lockdown was not in sight. State control units were proliferating, and the BOP was considering building a new, state-of-the-art federal control unit. It seemed as if we were banging our heads against a wall that wouldn’t give. At the same time, the prisoners were increasingly protesting the water situation at Marion. Marion prisoner Bill Dunne had reported in his newsletter, the Marionette (April 21,1988), that a hearing was held at the prison to determine whether a lawsuit by Marion prisoners against the supplying of contaminated water should be certified as a class action. The suit was originally filed in 1984, some time after the toxic waste dump left by Sangamon Electric in the Crab Orchard National Wildlife Refuge was discovered to be leaking PCBs and other contaminants into Crab Orchard Lake, the source of the prison’s water.

The threat was serious enough to induce the town of Marion, also supplied by the lake, to change its water source. Former Marion Warden Jerry Williford even told prisoners of a government plan to drill a well for the prison, a plan that was later scrapped due to costs. No decision was made at the 1988 hearing, and none was expected in the near future.

Now, in 1989, political prisoner Tim Blunk had researched the situation and produced a document entitled “Health Issues at Marion.”

The Refuge where Crab Orchard Lake is situated is very large and spans four counties. It was formed in the 1940s at a time when many “defense” industries were brought into the area in response to war needs and the lack of jobs in the region. These companies polluted, dumped, and wasted like crazy, and then left. The toxic waste was universally undisputed, and the soil in many places was almost pure poison. For example, some soil levels were measured to be composed of 25% PCBs, one of the most poisonous of substances. Other toxic wastes abounded, like dioxins (the essence of Agent Orange), furans, and more. All of these toxins can cause enormous problems (neurological dysfunction, muscle disorders, aches, pains) when present in very small amounts, and death when present in slightly larger amounts.

In March, 1989 Steve wrote an internal CEML memo, “Some Thoughts on the Water Situation at Marion,” based on reading news clippings, legal documents, and government reports, as well as Tim Blunk’s analysis. In preparation he also made a trip to the U.S. EPA office in the Chicago Federal Building. The EPA had done massive testing of all toxic aspects of the Refuge and the Lake, and issued a report indicating that the Lake water was fine, consistent with the fact that PCBs are not water-soluble.

Steve’s memo noted that the EPA employee, a woman who appeared to be an idealistic scientist and not a bureaucrat, thought the EPA report, public for all to see, was accurate in this regard.

But what about the prisoners? The prisoners were reporting many symptoms that appeared to be a result of drinking and showering with contaminated water. Contrary to the prisoncrats, we were inclined to believe the prisoners. Again, what purpose would it serve for them to be fabricating these symptoms? Was the prison water contaminated or not? What should we think?

Steve’s memo reported that studies had found high levels of lead in deer that had been killed in the area, and other studies found high levels of PCBs in fish from Crab Orchard Lake, predominantly catfish and others that feed at the bottom. The concluding analysis was that one should not eat catfish and other fatty fish from that area. PCBs are not water-soluble, but generally fall to the bottom of the lake, and the fish eat the particles. PCBs accumulate by being passed from one organism to another. Thus, once a catfish consumes PCBs, it will be contaminated for life, and a human that eats this catfish will be similarly contaminated. (Note: There are thus now a major set of institutions and rules that discuss which fish one can eat, and hot debates ensue, including in newspapers that seem to disbelieve the government agencies.)

Some background information was intriguing as well. In the early 1980s a class action suit had been filed by a Marion prisoner regarding the water. A group of lawyers from D.C., Trial Lawyers for Public Justice, was handling the suit with attorney Steve Feinberg from Chicago. Although all official information suggested that the water was okay, the government and the BOP were furiously resisting Feinberg’s request to obtain a survey of the water and take blood samples from the prisoners. This, despite the fact that Feinberg stated openly that if the samples did not show problems, he would drop the suit. Nonetheless the BOP was denying access. If the water was okay, why was the BOP so dead set on preventing the testing?

My position was that not a single person should be forced to drink that water since no one really knew the previous, current, or future levels of toxicity. Based on all this uncertainty, there was no reason for the prisoners to be drinking and showering in the water. Our demand should be for a new water supply now. Any doubt should be cause enough for change—today. We should not have to wait until the water was demonstrated to be lethal.

We were aware that two years earlier Rev. Ben Chavis’ United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice had issued a study entitled “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” demonstrating that toxic waste sites were overwhelmingly located in communities of color. For example, three out of every five Blacks and Hispanics lived in communities with uncontrolled toxic waste sites—15 million Blacks and 8 million Hispanics.

It seemed a no-brainer. We all agreed we should pursue the water issue at the prison. The overarching issue of the lockdown was at an impasse. Of course we would continue to raise that in all our literature and at every opportunity. But the prisoners were demanding a change in the water, and it made sense to follow their lead and support their demand. Also, this was a finite issue, one we could possibly win. A victory in the work would be a boost to everyone’s morale. (The petition we utilized in the water campaign can be seen online.)

That winter our old friend Dave Dellinger, the elder statesman/ defendant in the Chicago 8 conspiracy trial, was invited to be an instructor-in-residence at the University of Illinois in Champaign. For a month or so he lived in Allen Hall, a student dorm where he conducted classes and workshops and conversed informally with the student body. During that time the students at Allen Hall invited me to come to Champaign in March, to show our video and talk about the situation at Marion. I was pleased to have the opportunity. I hoped some of the students would get involved in the work and join us in our spring activities. And it was always such a privilege to see Dave under any circumstances.

In April, one of the attorneys in Southern Illinois, Donna Kolb, forwarded a letter to us she had sent to Quinlan. She was furious. After an attorney/client visit, one of her clients had been accused of receiving contraband from Donna and was subjected to a rectal search in front of a video camera and placed in a dry cell (no plumbing of any kind) for 24 hours. She suggested that the rectal search was conducted in violation of the regulations and that it was motivated by reasons entirely separate from any suspicion of contraband. She pointed out:

. . . during a legal visit a Control Unit prisoner is restrained by leg shackles and handcuffs which are covered by a black box restrained closely to a Martin chain around the waist. He must wear these chains throughout the entire visit, from the time he leaves the unit until he returns to his cell. While being moved, he is accompanied by three guards, two with clubs and one holding onto the handcuffs. While in the visiting booth, the prisoner is under constant surveillance by the visiting room guard. There is a camera mounted in the guards’ booth providing the capability of recording the entire visit on videotape . . . Under these conditions, it is physically impossible for a prisoner to conceal anything in his rectum.

Donna also described some of the measures of intimidation that she herself had been exposed to:

I have endured all manner of searches and investigation, including the use of dogs to smell my legal materials, my person, and the car I arrived in. My telephone conversations have been monitored, my office, home and car have been searched surreptitiously. My office has been burglarized, and only files of Marion prisoners removed. I have been personally threatened by guards, and I continue to be harassed by obscene telephone calls. Potential clients, members of the legal community, and total strangers have been told by government employees that I am a “gang associate” and under criminal investigation. I am being audited by the IRS. I cannot express vigorously enough that this harassment is entirely unjustified. . . .

Every aspect of my visit is monitored, and the institution has numerous copies of videotapes of my visits with my clients. Everything I carry with me is searched thoroughly each time I come to Marion. The records available regarding my conduct are so comprehensive that you can be assured there would be ample evidence of any illegal actions, if I were so engaged. In every instance, the searches have been fruitless, and the accusations have been made without any basis or foundation.

Meanwhile CEML had spent months gearing up for a demonstration in the area of Marion on Saturday, April 29, 1989. In March, we sent out “Save the Date” letters, announcing the cosponsorship of the demonstration with the National Committee to Free Puerto Rican Political Prisoners. The demands would be:

No More Contaminated Water at Marion!

End the Lockdown!

Abolish All Control Units—Everywhere!

End the Selective Mistreatment of Political Prisoners!

In the months preceding the demonstration, we made 30 presentations in Chicago, downstate Illinois and elsewhere. This would be a multifaceted action rallying at six sites, and we hoped to have more people than ever before. We printed thousands of flyers. A great deal of planning went into each and every part of the day. This involved, once again, renting buses, providing for food and drinks, dealing with publicity, tactical leadership, media spokespeople, planning the route and parking for the buses, ensuring that people could have access to bathrooms throughout the day, banners, placards, bullhorns, photography, speakers, press packets, etc. And, again, all with no staff, no money, no nothing—except our willpower and our belief in justice. Members of the Committee made several trips down to Marion to garner support, and work with the folks down there to scope out the lay of the land and plan the logistics.

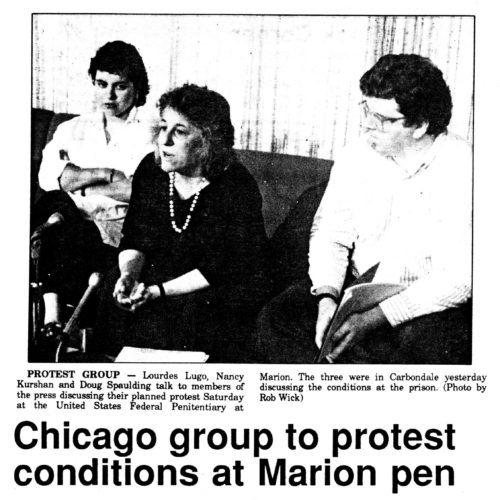

Three days before the protest, I traveled down to Southern Illinois, along with Lourdes Lugo, 22 the niece of Oscar López Rivera, who was representing the National Committee, and CEML member Doug Spalding. Facilitated by advance work by our friend Georgeanne and others, we held a press conference on Thursday, April 27th, at the Interfaith Center in Carbondale to announce our plans.

Everyone in the area knew we were coming. The towns down there, Marion and Carbondale, are small. The April 28th Marion Daily Republican printed a substantial story about our press conference on page 2 along with a picture of the three of us.

That same day a Guest Opinion entitled “End the Marion Lockdown” appeared in the Southern Illinoisan by Abbe Sudvarg, a family physician in nearby Murphysboro and a member of the local Southern Illinois Marion Prison Task Force. Abbe wrote:

. . . As I was finishing my undergraduate degree in 1979 and 1980, I worked with an organization in St. Louis whose goal was to end the control unit at the Marion prison. We believed that solitary confinement for years at a time was cruel and unusual.

We were also concerned about allegations that prisoners were being beaten by guards, having urine thrown on them and being subjected to strip searches and rectal probes without just cause. We were concerned because the men confined to the control unit were not necessarily the more violent prisoners but the more defiant. The control unit was being used to silence critics of prison policies, religious leaders and economic and philosophic dissidents within the prison system.

In late 1980, I moved away from St. Louis to go to medical school and, like most of us, I forgot all about the prisoners at Marion. It was easy to forgot them. I had never been to jail and none of my family or friends had ever “done time.” But now, in 1989, I find that I cannot continue ignoring those prisoners. Living and working in Southern Illinois, I am aware the Marion prison is only about 30 miles away, and it is worse than ever.

. . . Although it would be easy to forget the men at the Marion prison, many of us cannot forget. Tomorrow, concern for those men will be demonstrated by more than 200 people gathering at the prison with a very basic but very unyielding message: The cruelty within the walls of Marion Prison must end.

We had the greatest respect for people like Abbe and Georgeanne, the local people who were willing to come out publicly to protest the conditions at the prison. These were small towns where many of the prison guards and administrators lived. People they worked with and interacted with every day would know they had taken a stand.

Steve, who stayed behind in Chicago, told me that the night before the demonstration those people who were to be guides gathered as planned at the Puerto Rican Cultural Center at 10:30 p.m.. We had stressed in advance that the schedule was tight and people had to arrive on time. Everyone else arrived at midnight as requested and the four buses departed at 1 a.m. sharp. They had to ride through the night to accomplish what we had planned.

Saturday morning Georgeanne and I rose early, made coffee in great big coffee urns, and, with Doug’s help, brought them to the University campus where we anxiously awaited the buses. At 8 a.m. we were excited to see all four buses pull into the pre-planned spot where people scrubbed up, had coffee, donuts, etc. Cars also arrived from St. Louis, Charleston and Champaign (Illinois), Madison, Iowa City, Davenport, and others from the local area. From 9 to 10 a.m., there was a brief introductory rally at the Free Forum area on the campus of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, the first of our six pre-planned rally sites. I moderated at the first three rally sites. Here I explained the logistics and that we were going to be walking and on our feet a good part of the day, and if people were unable to do all that they could choose to ride in cars that Tom, a local organizer, had mobilized. We also heard from southern Illinois activist Jan Slagter and attorney Donna Kolb.

We then stepped off for a half-mile march to the Federal Building in downtown Carbondale. Since the prison is a federal facility, the U.S. government is really where the buck should stop. At this site representatives of several movement groups such as Act-UP, the Pledge of Resistance of both Carbondale and Chicago, the Illinois Coalition Against the Death Penalty, and the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee all gave brief greetings of support. We then walked 1.5 miles to the Carbondale Post Office, out along Route 13, the main highway in southern Illinois, in order to gain maximum visibility. We passed out leaflets to all takers, heard a message from the Freedom Now Campaign, the group that had formed to address the issue of political prisoners. I then requested that people hop back on the buses for a four-mile ride to Crab Orchard Lake.

The lake, the source of the contaminated water, is ironically a pastoral, idyllic spot. By now it was noon. People spread out on the grass and took the opportunity to eat lunches that were provided by a local restaurant, while Steve moderated the rally. Several messages from prisoners were read and other statements of support were offered by the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee and the No Pasaran Women’s Affinity Group. An enormous human billboard was set up along Route 13 by the Free Puerto Rico Committee. Each person held a letter and the whole group spelled out “NO POISON WATER AT MARION PRISON.”

After an hour and a half we boarded the bus to head off for the 6-mile ride into the countryside where the prison is located, as close to it as they would allow us to go. Although it was now about 3:00 p.m., and we had been demonstrating since 9:00 a.m. after riding through the night, people’s energy rose to the highest levels as we approached the gates of the prison.

The Marion Daily Republican (May 1, 1989) would later report that “It was a hot day . . . with the humidity reaching nearly unbearable proportions, but that didn’t stop the group from walking down the road leading to the prison carrying two large signs that said “Stop the Lockdown at Marion Prison” and “Abolish Control Units Everywhere.” There were two pictures side by side, captioned “THE ACTION AND THE REACTION.” The action was a picture of us with our various banners described as “the nearly 200 protestors who peacefully demonstrated at the U.S. Penitentiary Saturday, while the picture at the right shows what was waiting for the group. The Bureau of Prisons had closed the gate and set up the sign ‘U.S. Government Property No Trespassing,’ telling the group that this was as far as they could go.” Our way was blocked by about a dozen armed Illinois State Police troopers.

The reporter, Rob Wick, described the composition of the group in the following way:

The protestors were of every conceivable size, shape, color or age. Many had the appearance of being old enough to have protested America’s entry into World War I, while others were in diapers, or not even thought about, when America was in Vietnam. The majority were college students from around the state, with some wearing tee-shirts emblazoned with the University of Illinois, Eastern Illinois University, and SIU-C.

We held our rally on the spot where the prison guards blocked us, read several more messages from the prisoners, and heard from some of the sponsoring organizations, including CEML, represented by Mara Dodge, and Darla Bradley, an ex-political prisoner speaking on behalf of the Plowshares movement.

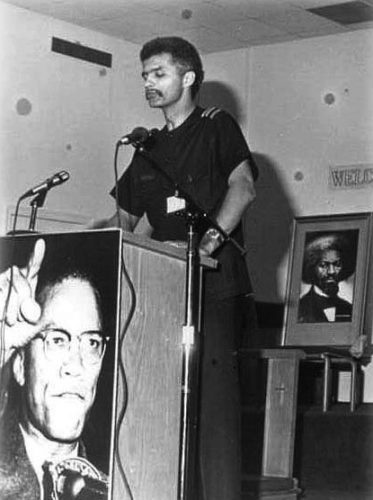

Chokwe Lumumba, the national chairperson of the New Afrikan People’s Organization, who had come from Jackson, Mississippi to be with us, delivered an eloquent and rousing speech. He pointed out that Marion was the sign of a sick society and indicated the foolishness of those who hope to cure the omnipresent problems with more prisons and more brutal repression.

We then re-boarded the buses for the eight-mile ride to downtown Marion where we marched around the city square, leafleted with a message prepared specifically for the people of southern Illinois, and held our final rally of the day—PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN ILLINOIS WE APPEAL TO YOU TO OPPOSE THE MARION LOCKDOWN.

The main speakers were Josefina Rodriguez from the National Committee and Cecil Reynolds who spoke for CEML and addressed his remarks to the townspeople of Marion. Josefina is the mother of two of the Puerto Rican political prisoners, Lucy and Alicia. Few people were better qualified to explain the relation between Marion, prisons, and repression of the Puerto Rican independence movement, and Josefina’s speech was a grand way to end the day’s demonstration. After a spaghetti dinner at the Attucks Community Center, we boarded the buses and headed home, arriving back in Chicago about 2:00 a.m. Sunday morning. In all we demonstrated for over eight hours and were gone for more than 26!

Apparently Randy Davis, Warden Henman’s assistant, held a press conference after we departed, attempting to refute our various allegations. He insisted that, “We are looking at alternative sources of water all the time, but if I didn’t think it was safe, do you think I would drink it?” We did not find that reassuring at all, particularly given the prisoners‘ consistent report that staff drank only bottled water—which was not provided to the prisoners.

The local media covered our demonstration generously. The article in the Sunday Southern Illinoisan was accompanied by a half-page picture of the protest showing our big banner, “Stop the Lockdown at Marion Prison.” The front-page headline read, “200 protest Marion ‘dungeon’” and the article reported that:

Speakers mixed their messages with music and poetry. They encouraged each other with cheers and applause, but they painted pictures darker than the morning storm clouds that threatened to pour rain on them. “We’re angry about the conditions that exist there,” said Nancy Kurshan of the Chicago-based Committee to End the Marion Lockdown . . .

Later on Marion’s Tower Square they pleaded with area residents not to sell their consciences for prison paychecks . . . the demonstrators were loud, but orderly . . . Chokwe Lumumba . . . told the group outside the prison that their presence was a “light in the midst of darkness.” . . . “The facts, of course, speak for themselves,” he said, “as we stand here around an institution surrounded by barbed wire, with men standing on the other side—men watching us being watched by other men who are watching them.”

Kurshan said the prison administration has perpetuated “a mythic story” about the institution and the men confined there.

“They would have us believe that somehow the men at Marion are the most demented forms of humanity that exist,” she said.

The reporter Rob Wick had no way of knowing how ironic his opening line was—“The only thing missing was Abbie Hoffman.” I smiled as I thought of my old friend from my yippie days and how proud he would be of us.

On Monday, May 1, the SIU student paper, The Daily Egyptian, reported that, “About 250 people from nine cities and seven college campuses throughout the Midwest converged in Carbondale to protest what they view as human rights violations at Marion Penitentiary.” They quoted Steve: “We have people here who have been traveling twelve hours to get here. They’ve spent their own money and time because they care about justice in this country.” I was quoted as stating that the prison is a “dungeon” where prisoners are treated “like animals in a zoo.” The final line of the story was, “Julie Jones of Davenport, Iowa said she and four friends drove all night to reach the Carbondale protest as ‘a matter of principle.’ ‘We have to oppose injustices wherever we find them. That’s the only way we can survive,’ she said.”

The most heartwarming responses came from some of the prisoners themselves. One prisoner wrote:

Thank you so much for the CEML and all your efforts to end this painfully long lockdown. It is so good of you to not scatter and run when the BOP flexes its muscles and growls that there is no more lockdown, it’s just high security. And oh! your rally and march were the best thing that’s happened in ages! Why were the guards so agitated all day, making rounds every 20 minutes, so grim-looking? The event was on all the channels and you could hear the guys clicking stations, yelling out “six!” “three!” and so on. Those of you who spoke were cogent and forthright and so you came across honest and concerned. It was most impressive. And we convicts really appreciated the collateral emphasis on the toxic drinking water. The prison mouthpiece who assured y’all (and the citizenry) that he drank the same water is surely a liar. The drinking water jokes are (always have been, I’m told) an ongoing sick-joke game among the guards. It is a struggle, sometimes, to not get discouraged and resigned: everyone knows that. I don’t know who you folks have to encourage you on but we have you. Thank you.

We also received support from political prisoner Bill Dunne:

From what I saw, the demonstration was great. The three local network affiliates aired about a minute each at 10:00 p.m. on the 29th, all at the same time. The NBC affiliate, WPSD-6, Paducah, Kentucky, showed a brief clip on its 6:00 p.m. report . . . Reaction here was universally positive . . . I think there was much sentiment that appreciated the fact that people would go so out of their way on our behalf. It helped break the isolation. And there is also the consciousness that even if such protest doesn’t wreak immediate change, it puts the swine on notice that they are being watched and that these dark concrete corners are not as lightless as they’d like. People know that that is something that stays the hand of abuse. And there is no doubt that such events help get the word out. Even if it just has to be by word of mouth, the organization of the demo helped put it in a lot of mouths . . . you have (individually and collectively) my/our appreciation and commendation for a fine job.

At the beginning of April, we had mailed a letter to each of our prisoner contacts inside Marion, asking if they would like to send a message to be read at the April activity. Every one of them informed us once again that they had not received the letter.

In mid-May, weeks after the demonstration, we received a package from the prison containing all the letters, each with a note saying that our correspondence has been determined detrimental to the security, good order, and discipline of the institution.

In June, Steve sent off another of his “reasonable” letters to Warden Henman. Never one to mince words, he wrote:

Not only are these claims preposterous and insulting, but the fact that you deliberately held the letters so that our communications with the prisoners would be prevented until after the demonstration is obvious. Fortunately, neither we nor the prisoners are as ignorant as you and messages from 13 different prisoners still reached us and were read and passionately appreciated by those of us standing in front of the gates of hell that you run, the lake from which you draw contaminated water for the prisoners in an effort to make them sick, and three other sites in the area.

As I wrote to you last time, no one expects you or Director Quinlan to act like human beings. We understand who you are and what your function is. The only surprising aspect of this entire matter is that each time you are caught doing acts like this, you deny them and act hurt and offended. But you never stop doing them. At least you’re consistent!

Meanwhile, health complaints from the prisoners continued unabated. Now there seemed to be an outbreak of giardia. Puerto Rican political prisoner Oscar López Rivera wrote to his family and supporters on the outside about the widespread symptoms inside Marion and asked us to pursue a remedy.

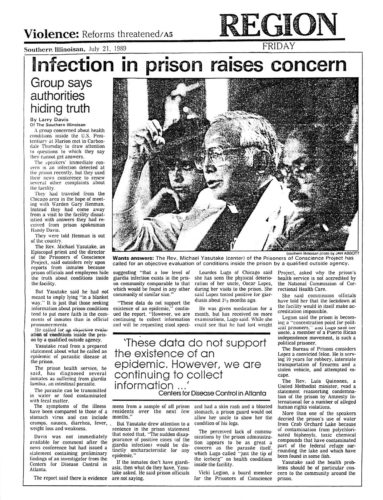

Rev. Michael Yasutake (affectionately referred to as “Yasu”) of the Interfaith Prisoners of Conscience Project led a delegation to Marion in the hopes of speaking with Warden Henman, but was told Henman was out of the country.

Yasutake and others then held a press conference calling for an objective evaluation by a qualified outside agency. Lourdes described the physical deterioration of her uncle, Oscar, since he was diagnosed with giardia three-and-a-half months ago. Yasu explained that “outsiders rely upon reports from inmates because prison officials and employees hide the truth about conditions inside the facility… those seeking information about prison conditions tend to put more faith in the comments of the inmates than in official pronouncements.”

All this attention had forced the prison to bring in the Centers for Disease Control, which claimed the data did not support the existence of an epidemic in Marion, but added that they were still studying the situation. Yasutake asked if it was not giardia, then what was it? There was no response. The headline in the Southern Illinoisan (July 21, 1989) read “Infection in prison raises concern.”

In August the U.S. EPA held a public hearing to explain their feasibility study for Crab Orchard. Their newsletter announced U.S. EPA Proposes Cleanup Action and described a process to “accept oral public comments on the cleanup alternatives.” We were encouraging people from around the country to bombard the prison with letters of concern.

In October, Don Schrader of Albuquerque forwarded a letter he received from Warden Henman, in which the Warden insisted that he and his family utilize the water on a daily basis as does the rest of the institutional staff. Our concerns were not assuaged. If that were the case, why were they reportedly looking for an alternative water source, why were they refusing to have an independent testing of the water for the class action suit, and why were the prisoners insisting that guards were carrying in their own water supply?

Also in October, 1989 the National Interreligious Task Force on Criminal Justice took up an offer to visit that Quinlan had proposed when the delegation met with him earlier that year (April 1989). They would later issue a report (April, 1990) entitled “Marion Prison: Progressive Correction or Legalized Torture?” in which they concluded: The absence of balance in the procedures at Marion prison, where security measures override the individual need for human contact, spiritual fulfillment, and fellowship, becomes an excuse for the constant show of sheer force. The conditions of Marion prison discussed in this report constitute, in our estimation, psychological pain and agony tantamount to torture.